The case about Astro

Justin Ahinon

Last updated on

For several years, I have more or less stayed in the “WordPress bubble”. My experience as a developer has been largely focused on creating for the CMS and then contributing/maintaining it full time.

But this never really affected my very curious and eager to learn nature. So during these years, I continued to explore other technologies, paradigms, frameworks, etc. in the web development sphere.

I tried JavaScript frameworks like Vue.js, headless frameworks like KeystoneJS, headless CMS like Forestry, DatoCMS, GraphCMS, static site generators like 11ty, Hugo or Gatsby.

I see all these explorations both as a desire to learn, but also as an attempt for me to find what attracted me most in software engineering.

And then I discovered Astro

I am very curious about web performance. That’s a bit of what is behind my interest in static site generators. I tried several of them for personal projects, I even created a starter template for one of them.

But so far, there has been only one that I liked/interest me enough to finish a project with (this site), and decide to talk about it (this article). That generator is Astro .

Enter Astro

Astro defines itself as "a new kind of static site builder for the modern web ". And in essence, that’s what it is. A tool that generates static pages.

But beyond that, Astro comes with a number of features, a way of looking at things that make it more than a static site builder. It is about these features and this philosophy that I am going to talk today.

Zero client-side JavaScript by default

I think the flagship feature of Astro is that it delivers no JavaScript to the client by default. Basically, what Astro does is to compile your code in HTML, CSS and JavaScript (the one you wrote, not the one from the framework) and send that to the browser

It’s like writing vanilla HTML+CSS+JavaScript directly, but with superpowers.

This feature has both interesting advantages, but also some disadvantages. Since all this compilation phase happens at build time, you can quickly end up with very long build times depending on the amount of content.

Partial hydration

I don’t think we can talk about Astro without mentioning partial hydration. I must confess that this is a concept I haven’t fully grasped yet, but I’ll try to describe it as best I can.

Let’s say you have a counter component written with Svelte as follows:

code loading...

You can import this component for use in Astro by doing this:

code loading...

By default, Astro does not send JavaScript to the client, so the component will not be interactive. It’s just HTML markup that is returned:

code loading...

This is where partial hydration comes in. By using client directives, we can explicitly tell Astro in which situation we want to make our Svelte component interactive. This can be as soon as the page loads, as soon as the component is visible in the viewport, depending on certain viewport sizes, etc.

Let’s add a directive to our component to hydrate it when it becomes visible in the viewport, then inspect the "Network" tab of the browser to see what happens:

code loading...

Notice that as soon as the component becomes visible, Astro injects the necessary JavaScript to make it fully functional (JavaScript from Svelte).

However, the other pages of the site will remain static , and will never receive this extra JavaScript code, unless the component is added with a client directive. This is what makes partial hydration interesting. You can make parts of your site dynamic without affecting the performance of other pages .

It should be noted, however, that to make hydration possible, Astro, adds a script to the page (to determine when the component to be hydrated meets the criteria specified by the directive) .

Bring your own framework

With the example above, you could see how straightforward it is to integrate a component from another framework into Astro.

The process can be summarized in three steps:

Install the framework :

npx astro add svelteCreate the component

Import it in a

.astrofile.

Astro makes this behavior quite easy by providing integrations for most popular component frameworks like React, Lit, Svelte, Vue, etc.

In my opinion, this is a very interesting feature because it opens the door to more advanced creations than a simple static site with Astro.

Personally, I think Astro could take this concept a bit further by creating a native way to manage the state for Astro components, and why not, extend this state to components imported from other frameworks.

The Astro language

If you know HTML, you already know enough to write your first Astro component.

— https://docs.astro.build/en/comparing-astro-vs-other-tools/#astro-vs-jsx

That’s what the Astro documentation says about the language. And I think there is no better way to define it. That’s also the first thing that struck me when I started using it. There’s not really a learning curve.

In fact, you can have a .html .html file, change its extension to .astro .astro and you have a totally valid Astro file . The Astro language is HTML with superpowers. It allows you to do most of the things that are possible with tools like JSX (conditional rendering, attribute spreading, etc.), but with a disconcerting ease.

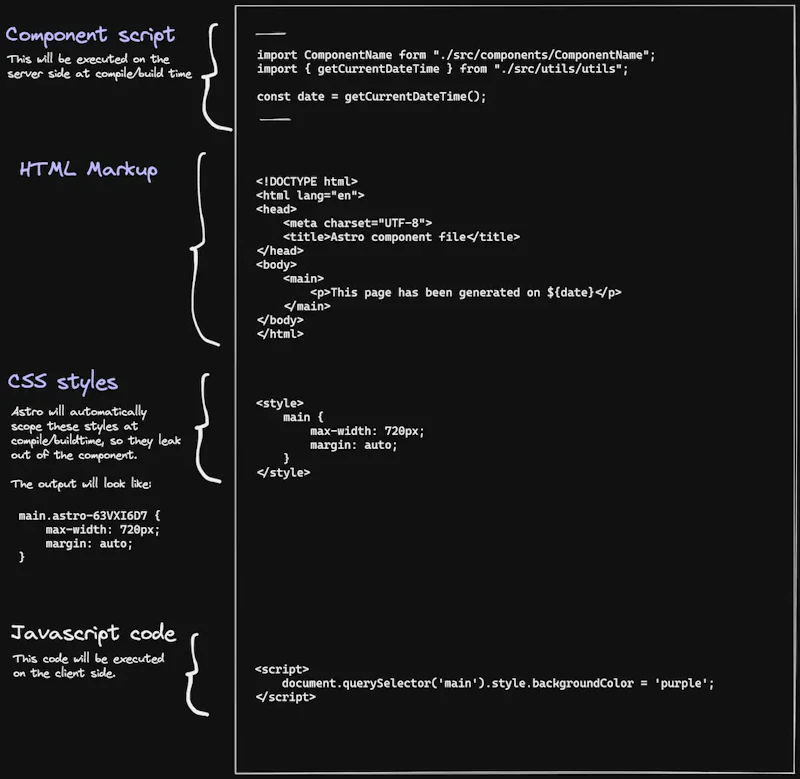

In general, a component written in Astro will look like:

Data fetching

By default, an Astro component allows to use the global JavaScript method fetch() in the component’s script ( which is enclosed by two pairs of dashes and placed at the top of the .astro .astro file ). So you can easily make API calls in the component, and pass the results to your HTML markup in the same file.

code loading...

As you can also see, you can also take advantage of the top-level await in your Astro component scripts.

The documentation

Well, let’s say it, Astro’s documentation is just very excellent. And it comes from someone who has significant experience with building documentation systems for Open Source projects.

This will, in my opinion, play a very important role in its adoption. The concepts are well explained and accompanied by code snippets to illustrate them. The organization of the documentation also makes it quite easy to navigate, which is an important point for new adopters of the tool.

In addition to the very rich documentation, Astro also has a very lively and active community on Discord. There is a dedicated support team that helps with community questions. Take a look, you won’t be disappointed.

Final thoughts

I think what will make Astro successful is that it doesn’t force developers to give up their knowledge of vanilla web development to try to fit into a framework way of thinking.

I was recently reading an article by Das Surma about the abstraction of tools/frameworks on the web, and he said this:

If developers already have a skill but are forced to spend time learning a new way to do the same thing, frustration happens. Doubly so if there is no tangible benefit of doing it “the new way”, apart from maybe idiomaticism or purity.

Do you know that feeling when you start using a tool, and you say to yourself: yes, this is the right one? A tool that makes me want to explore it, to discover its potentialities? This is the feeling that Astro gives me now.